Stargazing Guide to the Top December Constellations & Their Brightest Stars

Enjoy the December night sky by spotting Perseus, Eridanus, Cetus, and other beautiful constellations! With the free Star Walk 2 app, finding them is easy — it only takes a few seconds. In this article, you’ll learn other simple ways to find the must-see December constellations, the best times and directions for viewing them, and more.

Contents

List of December constellations

Each month has its own set of best visible constellations — those reaching their highest point in the sky around 9 p.m. In December, these are Perseus, Eridanus, Cetus, Aries, Triangulum, Hydrus, Horologium, and Fornax.

Some of them are easy to spot, while others require darker skies and a bit more practice. Below, we give you reference points and directions for both hemispheres, assuming you’re searching around 9–10 p.m. local time (when the sky is dark enough). For a simple way to locate all constellations above you, use the Star Walk 2 app, where all constellations are available for free.

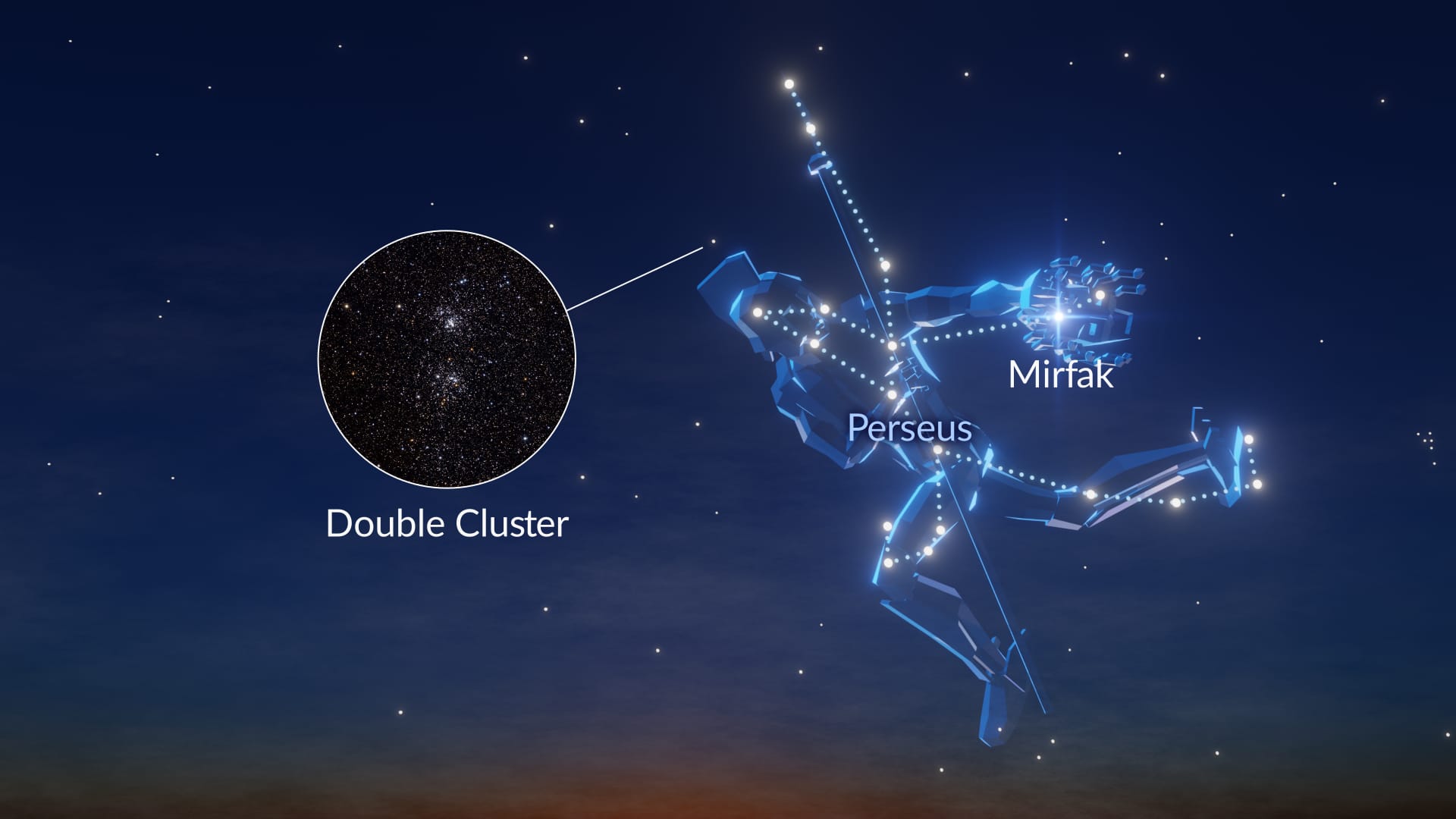

Perseus

- Brightness: ☆☆☆

- Visible from: 90°N to 35°S

- Brightest star: Mirfak (mag 1.8)

- Best deep-sky object: Double Cluster (NGC 869 and NGC 884, mag 3.8)

How to find Perseus in the December night sky

If you can find Cassiopeia — the bright M- or W-shaped constellation — you’re already halfway to finding Perseus. Perseus follows Cassiopeia across the sky, but its stars are dimmer, and its shape is less obvious, so a dark sky helps a lot.

In the Northern Hemisphere, Perseus is high overhead on December evenings. First, look up and find Cassiopeia’s “W” shape. Then look eastward to the bright star Capella (mag 0.1) in Auriga. Southwest of Capella, you’ll see the Pleiades, a compact, bluish star cluster. If you imagine a triangle connecting Cassiopeia, Capella, and the Pleiades, Perseus lies within it.

From about 40°N and farther north, Perseus asterism is circumpolar — it never sets but circles around Polaris, the North Star. In these regions (for example, the northern U.S. and Canada), Perseus is visible all night, year-round.

In the Southern Hemisphere, Perseus stays low above the northern horizon. South of roughly 30°S, you won’t see the full shape of the constellation. For example, in Sydney, Australia, Mirfak (the brightest star in Perseus) is visible, but the northern part of the constellation — including the famous Double Cluster — is too far north to rise.

Myth of the Perseus constellation

In Greek mythology, Perseus was the son of Zeus and the mortal Danaë, sent by King Polydectes on a seemingly impossible mission: to bring back the head of Medusa, the Gorgon whose gaze could turn anyone to stone. Perseus waited until night, when Medusa was asleep. Looking only at her reflection in his brightly polished shield, Perseus decapitated Medusa with one blow. When he beheaded her, the winged horse Pegasus and the warrior Chrysaor sprang from her body.

After this victory, Perseus traveled to the land ruled by Cepheus, whose daughter Andromeda was about to be sacrificed to the sea monster Cetus. Perseus slew the monster and saved Andromeda, later marrying her.

In the night sky, the constellation Perseus lies close to those of Andromeda, Cepheus, Cassiopeia (Andromeda’s mother), Cetus, and Pegasus — a celestial reflection of the myth’s interconnected characters and events.

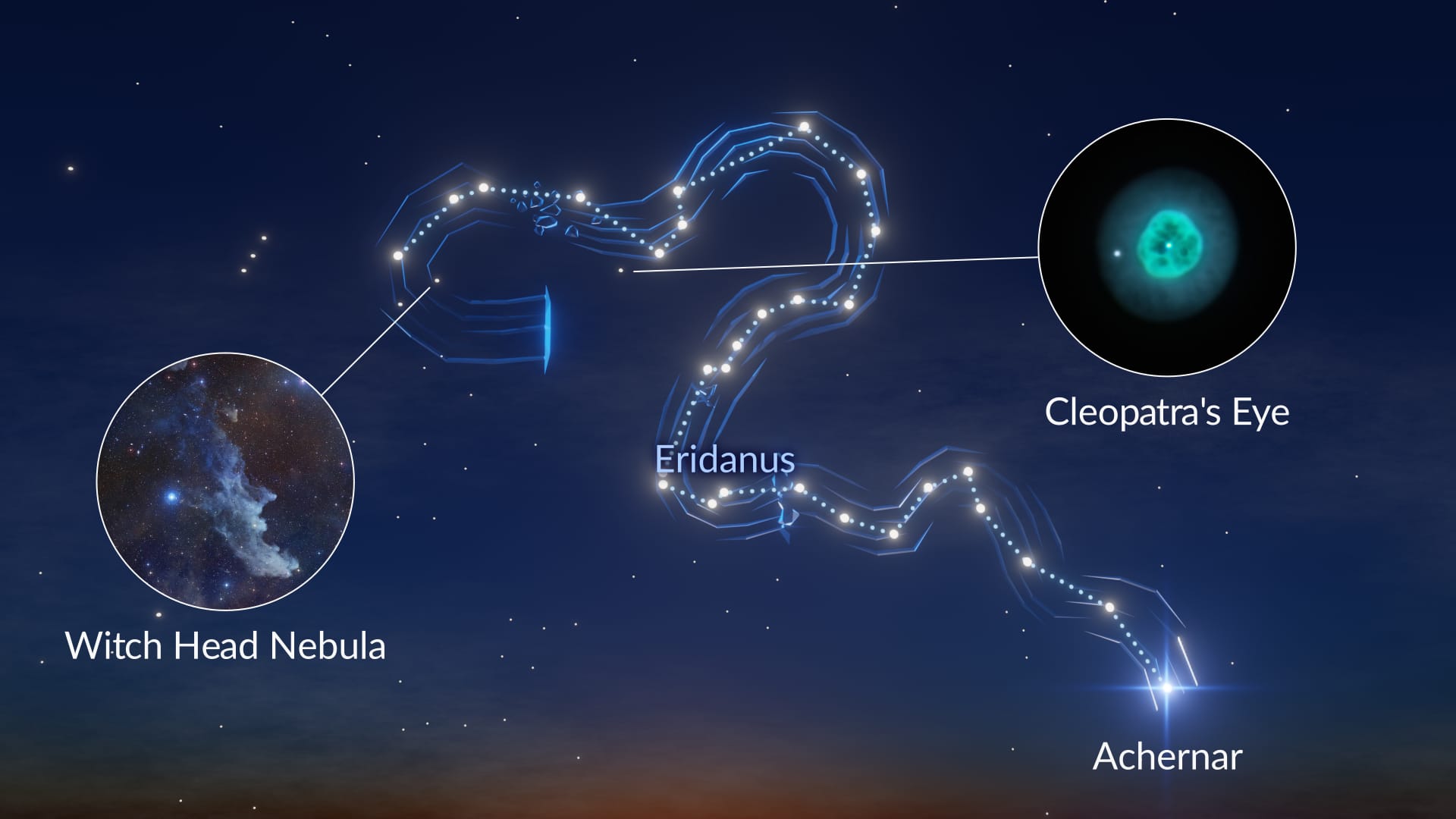

Eridanus

- Brightness: ☆☆

- Visible from: 60°N to 90°S

- Brightest star: Achernar (mag 0.5)

- Best deep-sky objects: Cleopatra's Eye (NGC 1535, mag 10.5), Witch Head Nebula (IC 2118, mag 13)

How to find Eridanus in the December night sky

To see Eridanus, you’ll need a truly dark sky — it’s too faint for city or suburban conditions. It’s one of the longest constellations, and has the greatest extent from north to south of any constellation in the sky!

From the Northern Hemisphere, look south. Use Orion as your guide: Eridanus begins near Rigel, Orion’s brightest star, rises in a big loop, then winds back toward the southern horizon. From most of the U.S., Eridanus’ southern end sinks below the horizon, so you can’t see its brightest star, Achernar, unless you’re at southerly latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere.

In the Southern Hemisphere, Orion still points the way: around 10 p.m., when the sky is dark enough, look above the northeastern horizon — you’ll find Eridanus above Rigel. Over the night, the constellation will move westward, setting around sunrise.

Myth of the Eridanus constellation

In Greek mythology, Eridanus is associated with the story of Phaethon, who tried to drive his father Helios’ (i.e., the Sun) chariot but lost control, scorching the Earth and the sky. To stop the disaster, Zeus intervened by striking him down with a thunderbolt, and Phaethon fell to Earth. Eridanus was said to mark the path Phaethon drove along — later seen as a route for souls.

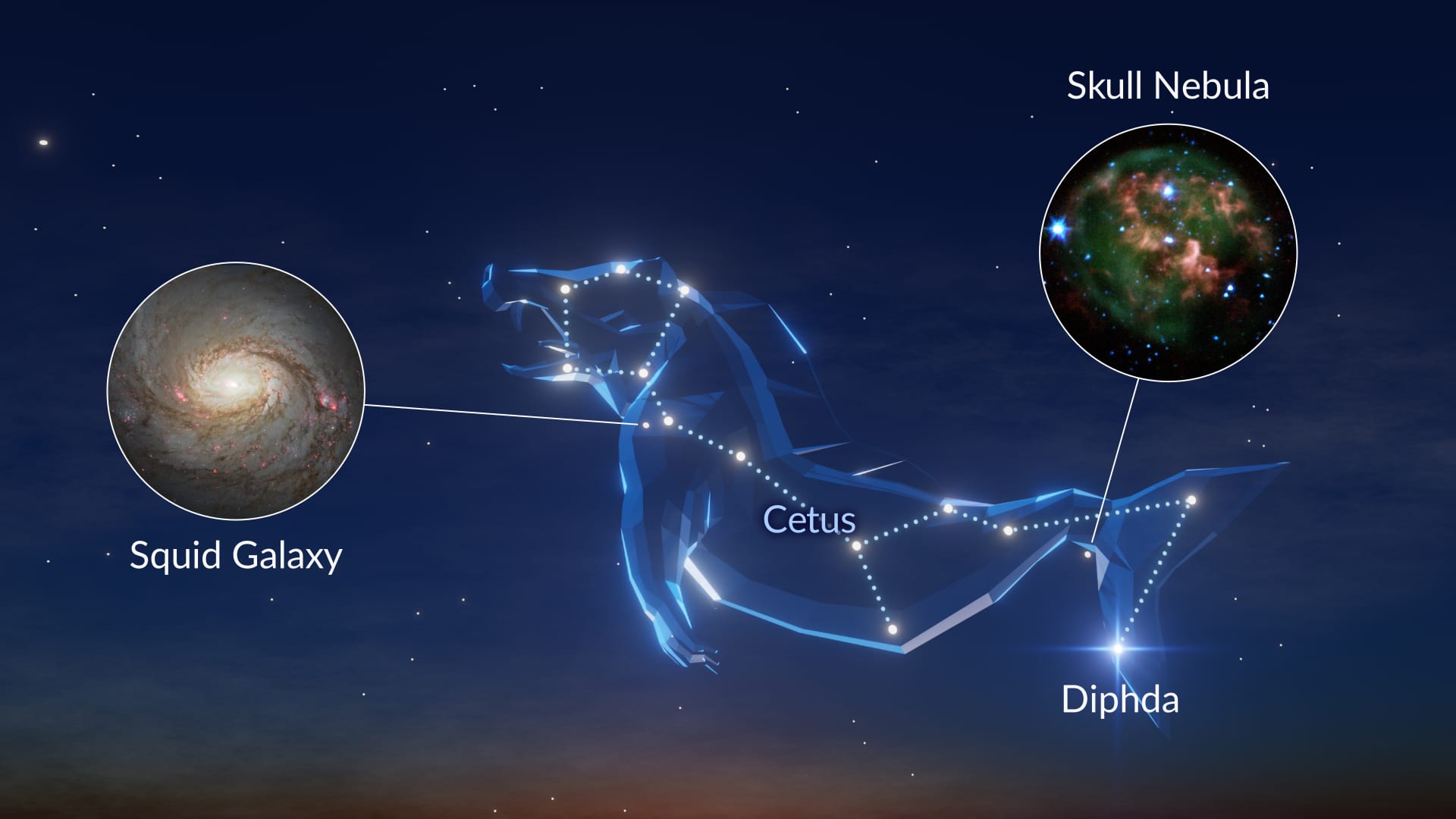

Cetus

- Brightness: ☆☆

- Visible from: 70°N to 90°S

- Brightest star: Diphda (mag 2.0)

- Best deep-sky objects: Skull Nebula (NGC 246, mag 8.0), Squid Galaxy (Messier 77, mag 8.9)

How to find Cetus in the December night sky

Cetus is the fourth-largest constellation in the sky — only Ursa Major, Virgo, and Hydra are bigger. It isn’t especially bright, but its position close to the ecliptic makes it easier to track down.

From the Northern Hemisphere, look low above the southwestern horizon. In December 2025, the first thing you’ll likely notice in that direction is the golden glow of Saturn, which sits near the tail of Cetus. About 20° to the left of Saturn (or two fists at arm’s length) is Diphda, the brightest star in Cetus. Toward the end of the month, the 42%-illuminated moon will pass west of Saturn while moving through Pisces.

From the Southern Hemisphere, Cetus sits relatively high above the northwestern horizon. Look for it above (south of) Saturn. You can also use Pegasus as a guide — the upper star of the Great Square points directly toward Cetus.

Myth of the Cetus constellation

According to Greek mythology, Cetus was a terrifying sea monster that nearly devoured Andromeda after she was chained to a rock as a sacrifice. Fortunately, Perseus arrived just in time to rescue her. In some versions of the story, Perseus killed Cetus with his sword. In others, the monster turned to stone when he revealed Medusa's severed head. In any case, Cetus was immortalized in the sky as one of the great constellations.

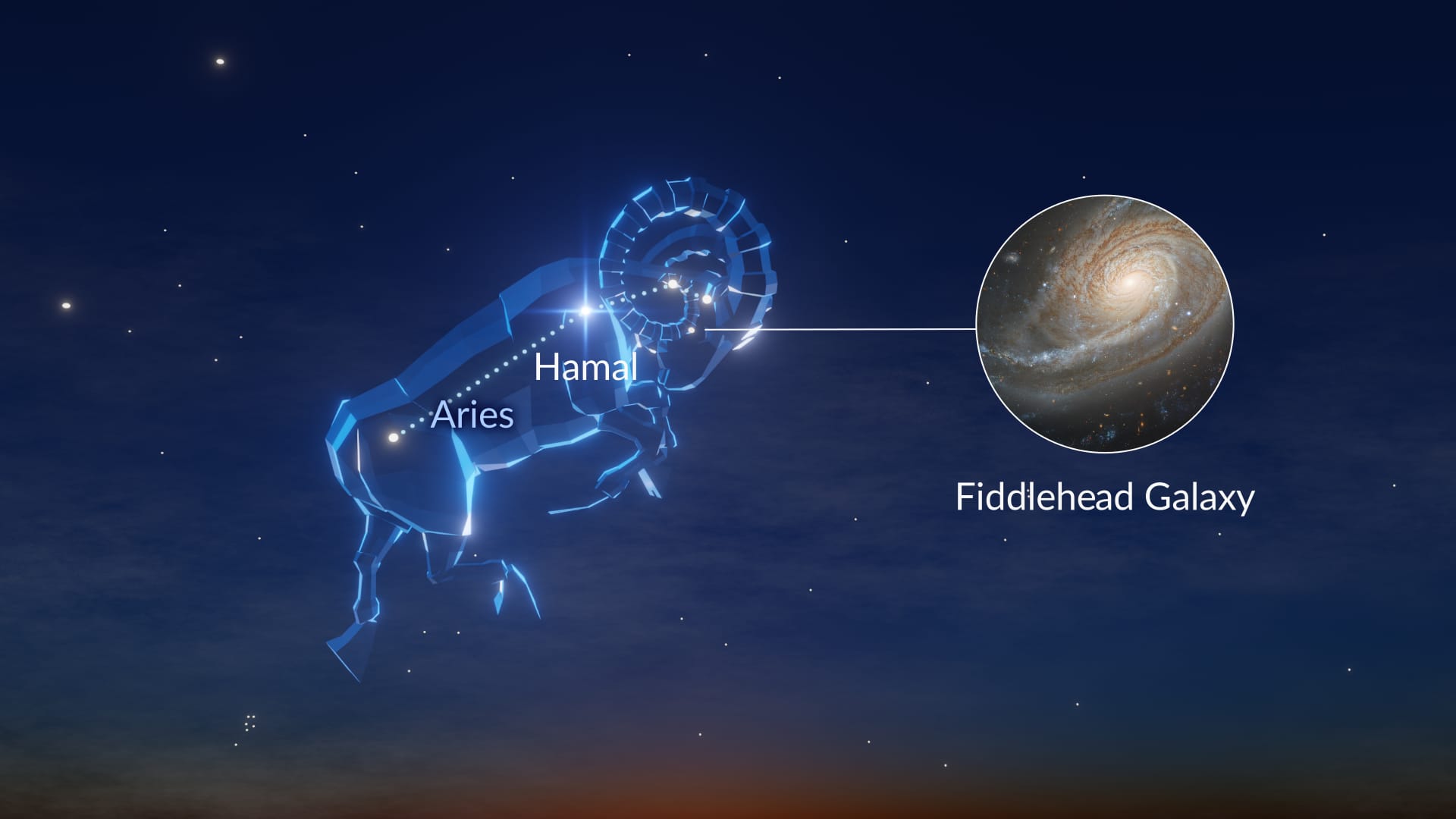

Aries

- Brightness: ☆☆

- Visible from: 90°N to 60°S

- Brightest star: Hamal (mag 2.0)

- Best deep-sky object: Fiddlehead Galaxy (NGC 772, mag 11.1)

How to find Aries in the December night sky

Aries isn’t a very eye-catching constellation. It’s the 11th smallest of the 12 zodiac constellations, and its stars are only moderately bright. Because it isn’t very prominent, you’ll need a dark, moonless sky to spot it easily. Under good conditions, the three stars that form the Aries’ head — Hamal, Sheratan, and Mesartim — stand out much more clearly, almost as if someone turned up their brightness. With a small telescope, you can also see that Mesartim is a double star.

Luckily, Aries is fairly simple to find. In the Northern Hemisphere, look southward and locate the area between two useful guideposts: the Pleiades star cluster to the east and the Great Square of Pegasus to the west. Aries lies right between them. If you’re observing from southern latitudes, use the same two reference points, but look toward the northern direction instead.

Myth of the Aries constellation

In Greek mythology, Aries is the golden ram that saved Phrixus and his sister, Helle. Their stepmother, Ino, hated them and plotted to sacrifice them by causing a famine and misinterpreting the oracle's message. Their mother, Nephele, sent a flying golden ram to rescue the twins. During the flight, Helle fell into the sea, which was later named the Hellespont. Phrixus safely reached Colchis, where King Aeëtes welcomed him and gave his daughter to him in marriage. To show his gratitude, Phrixus sacrificed the ram to Zeus and gave its golden fleece to Aeetes. The ram was then placed in the sky as the constellation Aries.

Triangulum

- Brightness: ☆

- Visible from: 90°N to 50°S

- Brightest star: Beta Trianguli (mag 3.0)

- Best deep-sky object: Triangulum Galaxy (M33, mag 5.7)

How to find Triangulum in the December night sky

Triangulum’s asterism is made of just three faint stars forming a small, simple triangle. Despite its modest appearance, the constellation has been known since ancient Greek times, more than 2,000 years ago.

Although its stars aren’t bright, Triangulum is fairly easy to locate because it sits near several well-known constellations — including Aries — and contains the famous Triangulum Galaxy (M33).

To find Triangulum, start by locating Aries. Then look just north-northwest of it for a small, elongated triangle of dim stars — that’s the constellation Triangulum.

Myth of the Triangulum constellation

Because any three stars can form a triangle, it’s not surprising that the sky includes a constellation shaped exactly like one. Ancient Greek poets and astronomers knew it well: Aratus and Eratosthenes called it Deltoton, since it resembled the Greek letter delta (Δ), while Ptolemy listed it in the Almagest as Trigonon, meaning “triangle.”

As for mythology, Triangulum is unusual. Unlike most constellations, it isn’t tied to a famous hero, creature, or dramatic story. One minor tale says the god Hermes created the constellation to help highlight the neighboring constellation Aries, giving it a fainter companion in the sky.

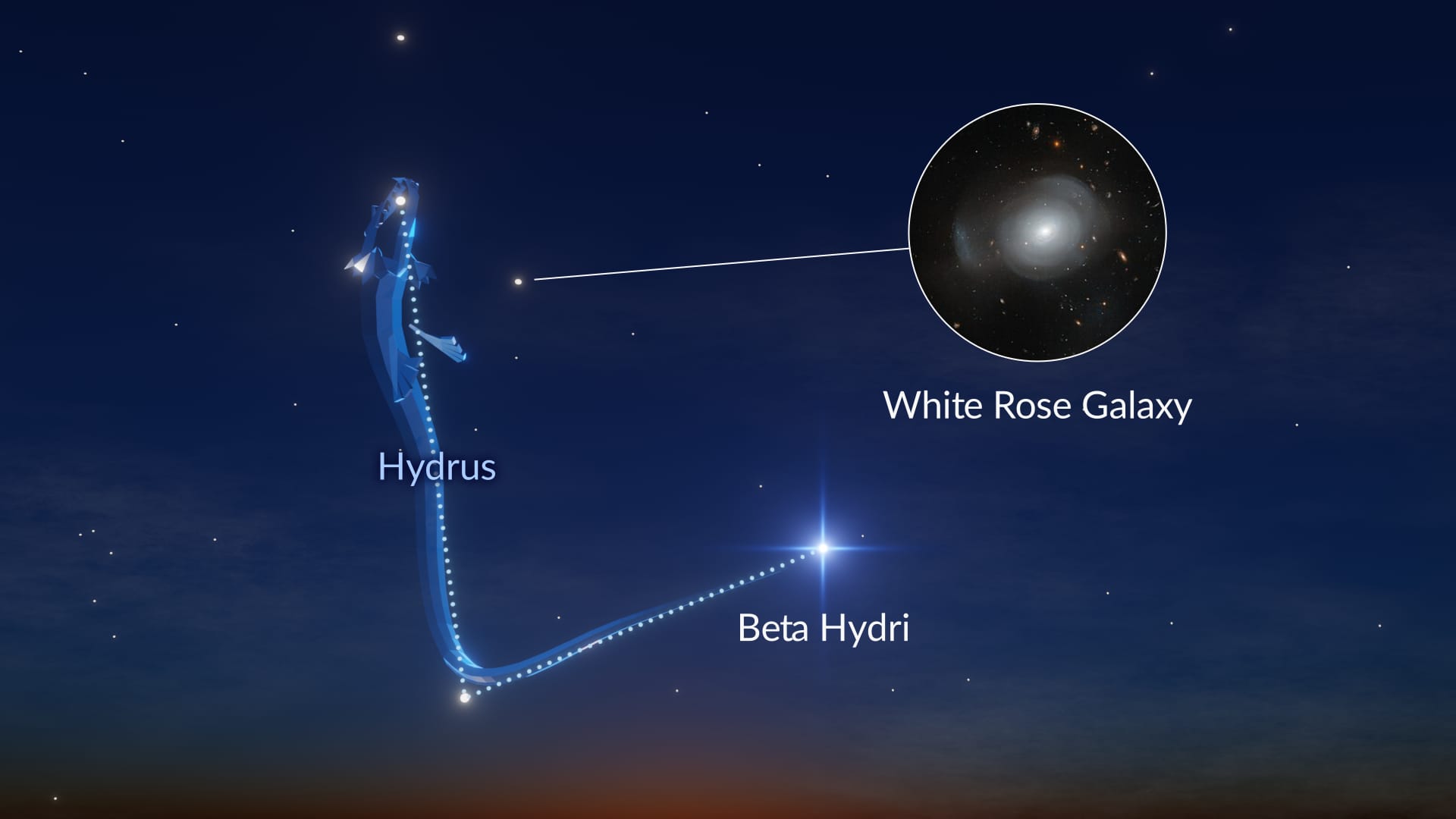

Hydrus

- Brightness: ☆

- Visible from: 5°N to 90°S

- Brightest star: Beta Hydri (mag 2.8)

- Best deep-sky object: White Rose Galaxy (PGC 6240, mag 13.3)

How to find Hydrus in the December night sky

From most of the Northern Hemisphere, Hydrus never rises above the horizon. Only observers close to the equator — for example, in Malé, Maldives — can glimpse it very low in the south, a bit east of Achernar in Eridanus.

In the Southern Hemisphere, Hydrus is much easier to see. It’s visible from all southern locations and is circumpolar (never sets) south of about 50°S. Its brightest star is Beta Hydri (mag 2.8), the closest reasonably bright star to the south celestial pole. To find Hydrus, look high in the southern sky and locate Achernar in Eridanus — Hydrus lies just below it.

Myth of the Hydrus constellation

The constellation Hydrus has no traditional mythological story attached to it. It is one of twelve southern constellations introduced in the late 16th century, based on observations by explorers Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman. Hydrus first appeared in a star atlas in 1603, in the German cartographer Johann Bayer’s Uranometria.

De Houtman also included it in his southern star catalog the same year under the Dutch name De Waterslang (“The Water Snake”). It represents a type of snake encountered on the explorers’ voyage, rather than a creature from ancient myth.

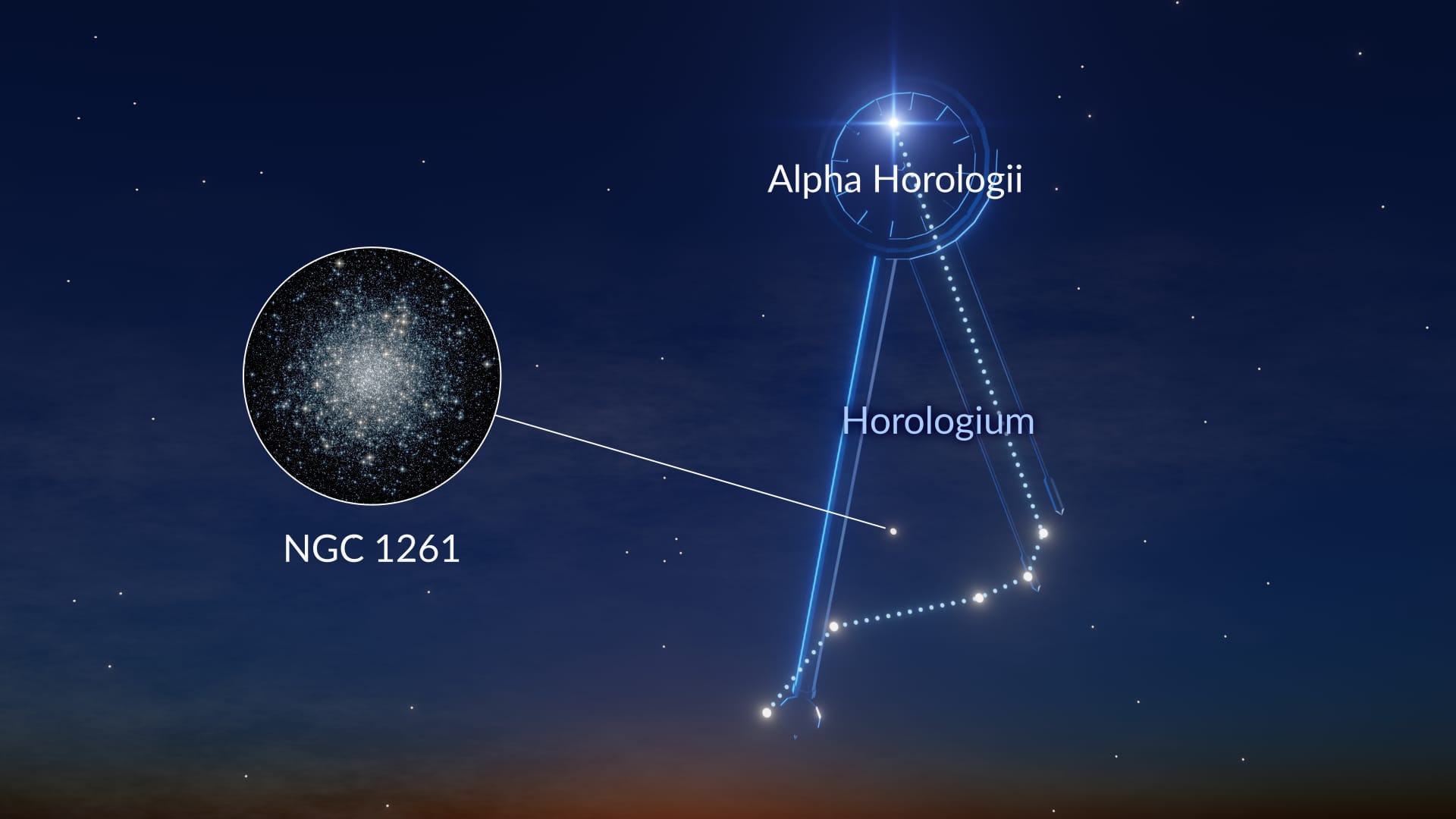

Horologium

- Brightness: ☆

- Visible from: 20°N to 90°S

- Brightest star: Alpha Horologii (mag 3.8)

- Best deep-sky object: NGC 1261 (mag 8.6)

How to find Horologium in the December night sky

Horologium’s main recognizable pattern is formed by six faint stars, and only one of them is brighter than magnitude 4. So you’ll need a dark, moonless sky to see the entire pattern clearly.

The easiest way to locate Horologium is by using two bright guide stars: Canopus, the second-brightest star in the night sky, and Achernar in Eridanus. If you draw an imaginary line between Canopus and Achernar, Horologium sits roughly halfway between them.

In the Southern Hemisphere, look high above the southern horizon to find the constellation. In the Northern Hemisphere, Horologium is not visible north of about 20°N. South of this latitude, it appears very low above the southern horizon.

Myth of the Horologium constellation

Horologium is a modern constellation with no ancient myth behind it. It was created by French astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille, who mapped the southern skies in 1751–52. He designed it to represent a pendulum clock beating seconds — the kind he used to time his observations. Lacaille first named it l’Horloge (“the clock”) on his 1756 star chart, and this was later Latinized to Horologium in the 1763 edition.

Fornax

- Brightness: ☆

- Visible from: 50°N to 90°S

- Brightest star: Alpha Fornacis (mag 3.8)

- Best deep-sky object: Robin's Egg Nebula (NGC 1360, mag 9.4), Fornax Dwarf (mag 9.3)

How to find Fornax in the December night sky

Fornax is one of the faintest constellations, so it’s easiest to find by using nearby bright stars as guides. A simple method is to draw an imaginary line from Rigel in Orion to Achernar in Eridanus — Fornax sits roughly halfway between these two bright stars.

If you’re in the northern latitudes, where Achernar isn’t visible, simply look toward the southern horizon — Fornax sits low above it in that part of the sky. From the Southern Hemisphere, Fornax appears much higher and can be seen nearly overhead.

Myth of the Fornax constellation

Fornax is a relatively modern and obscure constellation with no ancient mythology associated with it. French astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille introduced it after his 1751–1752 expedition to the Cape of Good Hope, during which he charted the southern skies. Lacaille depicted Fornax as a chemist’s distillation furnace and placed it in a bend of the celestial river Eridanus.

F. A. Q.

How to find constellations in the night sky?

Nowadays, you don't need to be a professional astronomer to locate the constellations and their stars — all you need is an astronomy app on your device. We recommend the Star Walk 2 app if you are more into stunning graphics and interactive 3D constellations, and the Sky Tonight app if you also want to explore the famous asterisms. Both apps are free and easy to use: just point your device at the sky and learn the name of any constellation or celestial object above you.

How many constellations are visible in winter in the Northern Hemisphere and in summer in the Southern Hemisphere?

The exact number of constellations visible depends on your location, time, and the amount of light pollution, but on average about 30 constellations can be seen in winter in the Northern Hemisphere, and about 40 constellations can be seen in summer in the Southern Hemisphere. How many of these can you name? Test your knowledge with our constellations quiz.

Why do constellations change with the seasons?

Due to the Earth’s orbit around the Sun, the constellations seen in the night sky change throughout the year. Those near the celestial poles, like Ursa Minor in the Northern Hemisphere and Crux in the Southern Hemisphere, remain visible all year and are called circumpolar constellations. Meanwhile, other constellations appear in the night sky only during certain times of the year and are known as seasonal constellations. Discover more about the seasonal constellations of the Northern Hemisphere and Southern Hemisphere.

Constellations visible in December: bottom line

December is a great month to explore both bright, story-rich constellations like Perseus, Cetus, and Aries and fainter southern sky gems like Hydrus, Horologium, and Fornax. Some of them are easy to spot with the naked eye, others need dark skies and a bit of patience — but each has something special to offer, from famous myths to beautiful star clusters and galaxies.

You don’t need to memorize star charts to enjoy them: just head outside around 9–10 p.m., let your eyes adjust to the dark, and use Star Walk 2 to guide you. Point your device at the sky, and let December’s stars tell their stories.

Learn what else to see in the December skies from our dedicated article.

Best visible constellations by months: