Apollo-Soyuz Test Project: The Cosmic Handshake Symbolizing the End of the Space Race

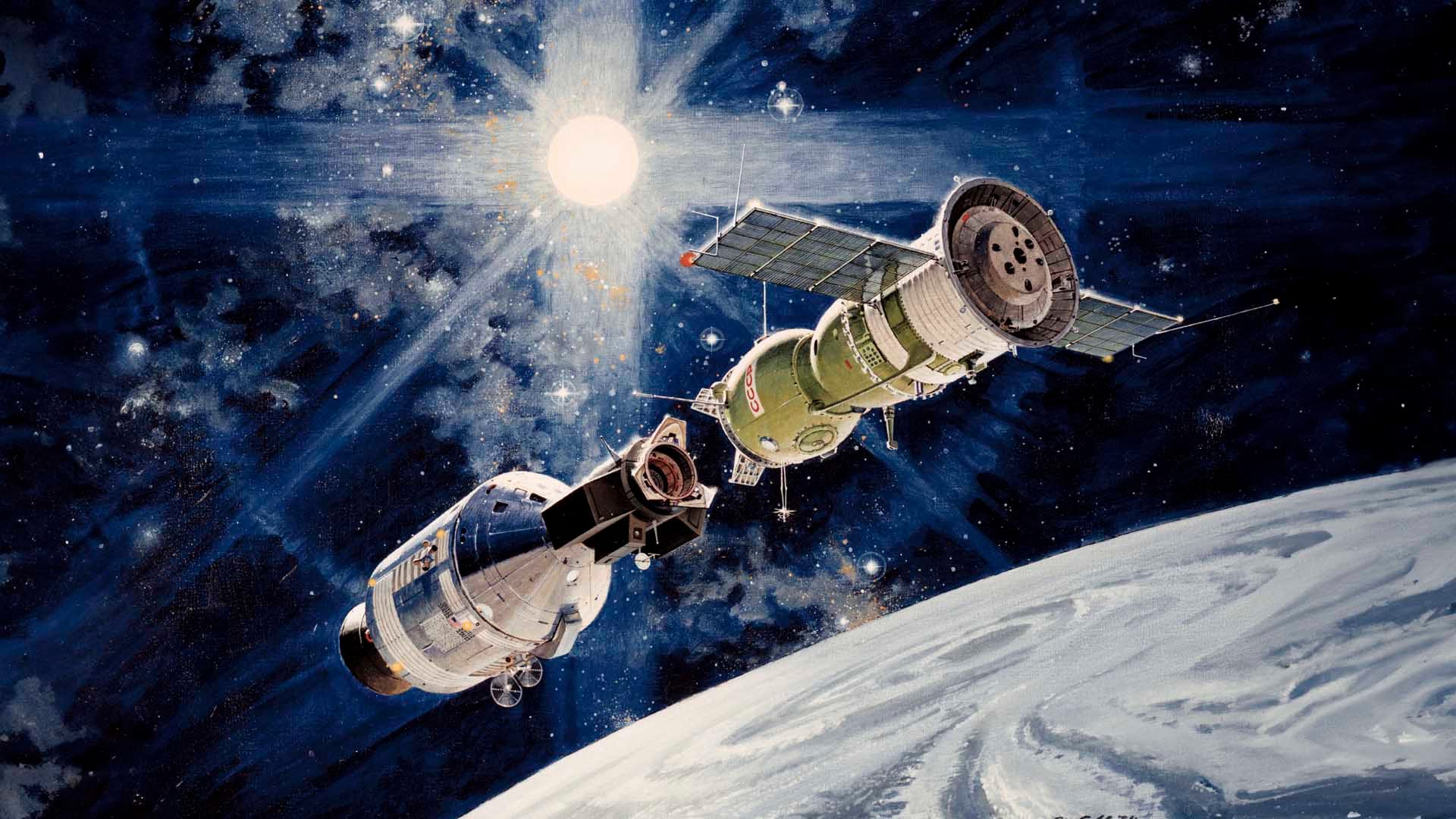

Fifty years ago, on July 17, 1975, the first international handshake in space took place. As the American Apollo spacecraft docked with the Soviet Soyuz in orbit, astronauts and cosmonauts — once fierce rivals in the space race — met with an open hand. Learn about this historic mission and enjoy fun facts, like the surprise stowaway on Apollo and how the crews found a clever way to overcome their language barrier. Let’s get started!

Contents

- What Is the Apollo-Soyuz Mission?

- Backstory: From Space Race to Space Embrace

- Apollo-Soyuz Mission Preparation: Training & Challenges

- Afterword: The Significance Of the Apollo-Soyuz Mission

What Is the Apollo-Soyuz Mission?

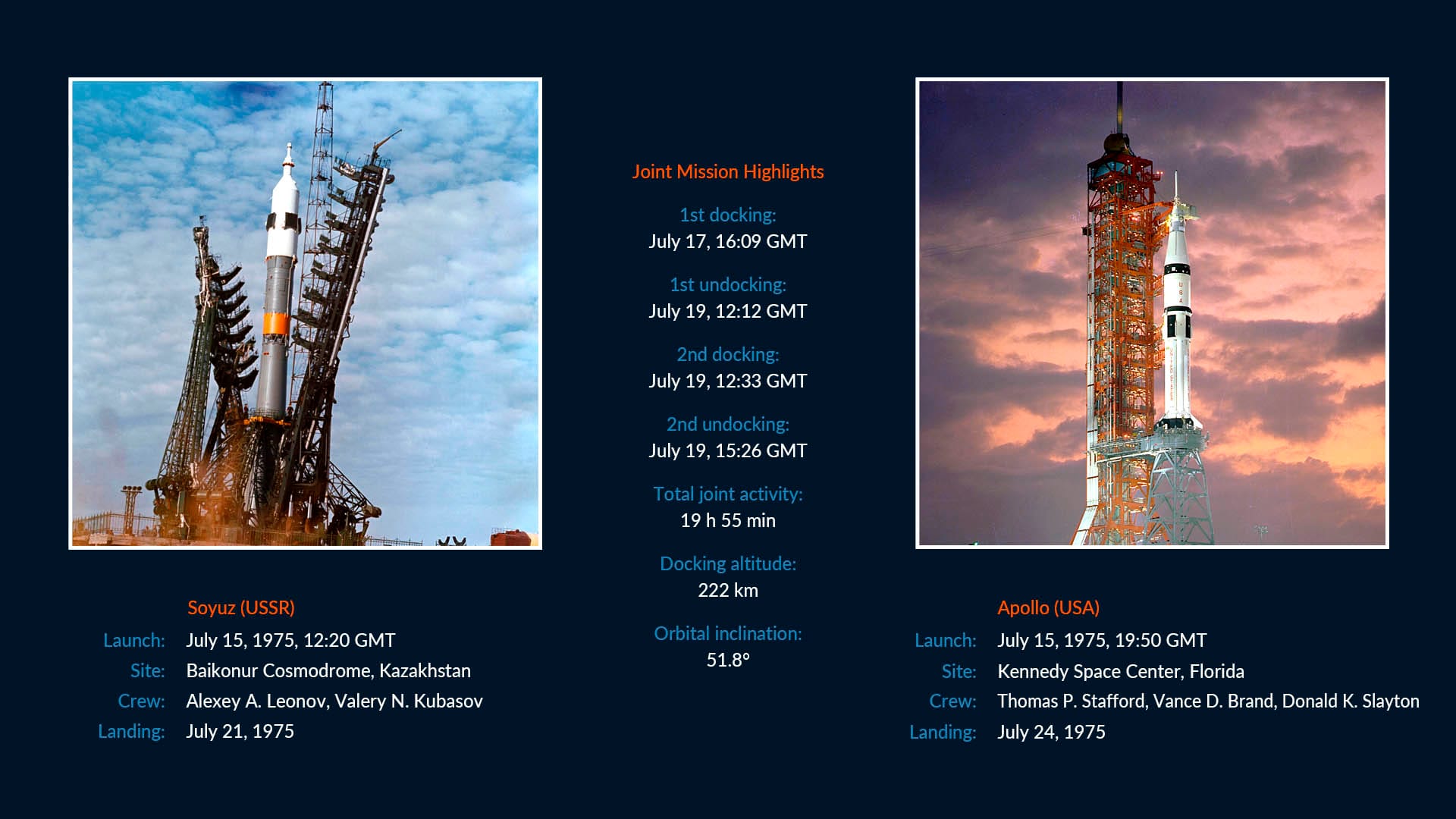

Apollo-Soyuz was the first joint space mission between the United States and the Soviet Union, launched in July 1975. For the mission, the American side launched the Apollo spacecraft from the Kennedy Space Center, and the Soviet side launched the Soyuz spacecraft from the Baikonur Cosmodrome. The two spacecraft docked in orbit, 222 km above Earth.

The mission’s goal was to test the compatibility of docking systems and to explore the feasibility of international space rescue operations. It is also widely seen as a symbolic end to the space race. Officially named the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP) in the United States and Experimental Flight "Soyuz-Apollo" in the Soviet Union, it was a historic step to future collaborations, including Shuttle-Mir and the International Space Station.

Backstory: From Space Race to Space Embrace

For nearly two decades before the Apollo-Soyuz mission, the United States and the Soviet Union were locked in a fierce space race. The Soviets claimed early victories with Sputnik in 1957 and Yuri Gagarin’s first manned space flight in 1961. The U.S. responded with the Project Mercury, Gemini, and ultimately the Apollo program, landing humans on the Moon by 1969.

But by the early 1970s, a period of détente emerged, and both superpowers recognized the value of collaboration. In 1972, during the Nixon–Brezhnev summit, the two nations signed an agreement for a joint mission. The result was the first Soviet-American flight, the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project.

Apollo-Soyuz Mission Preparation: Training & Challenges

From 1973 to 1975, the Apollo and Soyuz crews trained together at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston and the Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center near Moscow. Outside of simulator runs and engineering meetings, the crews bonded over shared meals and light moments, such as a snowball fight in Star City and a Lebanese dance performance at the Texas Folklife Festival. These cultural exchanges weren’t just fun; they laid the groundwork for trust and teamwork.

One of the earliest struggles was a language barrier. Initially, each crew spoke their own language, which made it difficult for the other crew to understand. The creative solution was a switch: the Americans would speak Russian, and the Soviets would speak English. This reversed approach worked perfectly — no one used sophisticated words, and communication flowed more naturally.

On the technical side, two major issues needed to be solved. First, the Apollo probe-and-drogue docking system was incompatible with the cone-shaped Soyuz design, so engineers developed a universal docking module. Second, the spacecraft had different cabin atmospheres: Soyuz used an Earth-like nitrogen-oxygen mix, while Apollo operated on low-pressure pure oxygen. This posed a risk of decompression sickness during crew transfers, which was resolved through pressure equalization protocols and pre-breathing oxygen for Apollo astronauts.

Preparing for the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project was also a diplomatic balancing act. Soviet engineers were nervous about revealing their classified technology, while in the U.S., the media and political critics questioned whether Soviet spacecraft were modern and safe enough to meet NASA standards. Fortunately, both sides found common ground. It wasn’t easy, but through patience, compromise, and a lot of joint problem-solving, the crews built the foundation for the mission. The handshake in space was preceded by months of handshakes in Houston and Moscow.

Apollo-Soyuz Flight Log

July 15: Two Launches, One Goal

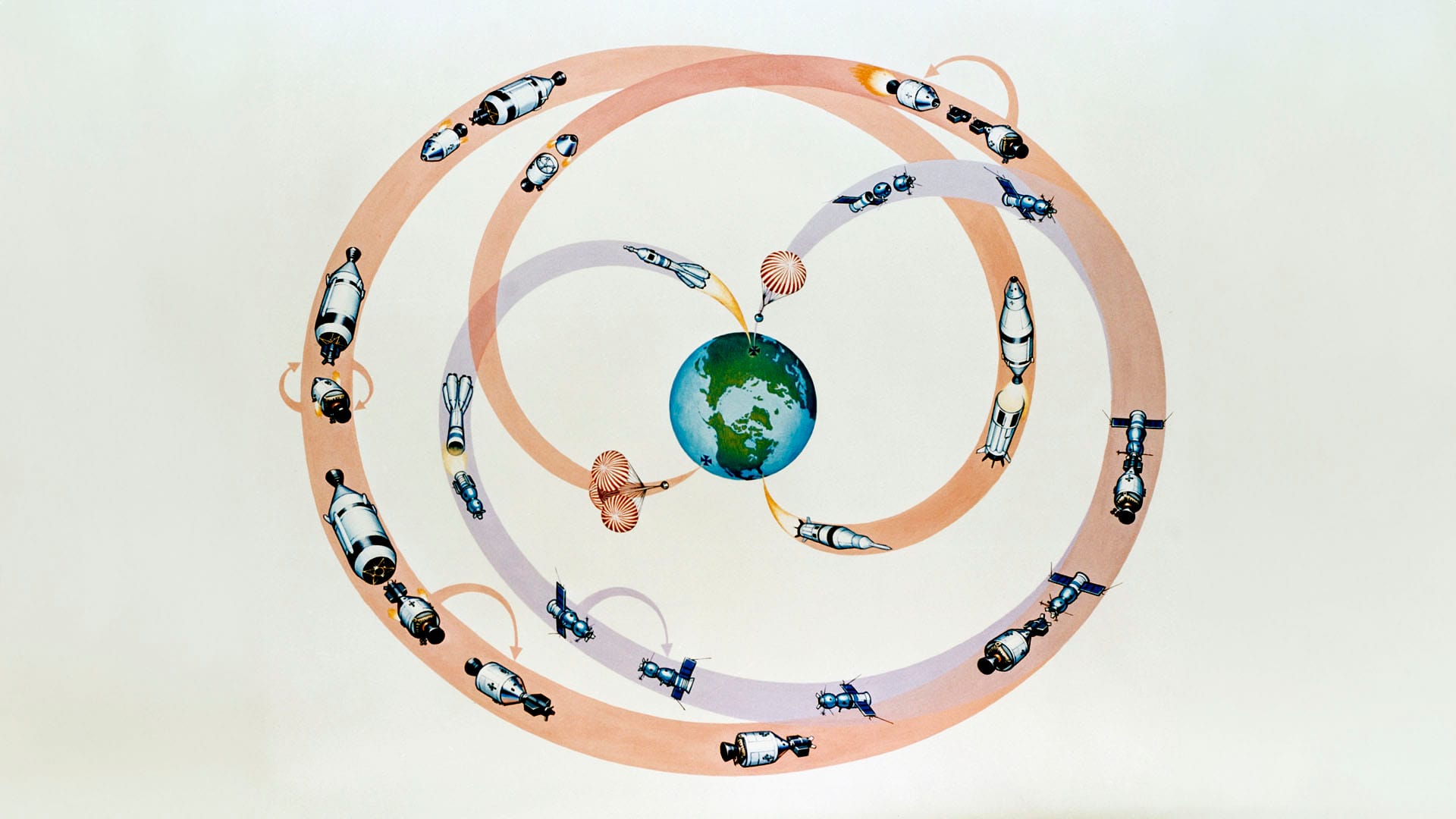

The mission began with two launches: Soyuz 19 lifted off from Baikonur at 12:20 GMT (15:20 Moscow Time), followed by Apollo from Kennedy Space Center at 19:50 GMT (3:50 p.m. EDT).

Soon after reaching orbit, Apollo performed a tricky maneuver to retrieve the docking module. Commander Tom Stafford was briefly blinded by sunlight reflected off Earth but managed to align the spacecraft manually with record precision of 0.01 degrees.

Meanwhile, the Apollo crew spotted an unexpected passenger, a Florida mosquito. Sadly or not, it disappeared a few hours later.

July 16: The Chase

Apollo’s day began with the sounds of Chicago’s “Wake Up Sunshine,” while aboard Soyuz, the crew was already awake, trying to fix their black-and-white TV system. The repair attempt failed, frustrating NASA officials who had hoped to get views of Apollo from the Soviet side. Still, the mission remained on track. Throughout the night, Apollo continued closing in, gaining about 255 km per orbit.

July 17: Apollo-Soyuz Handshake

On July 17 at 16:09 GMT, Apollo and Soyuz completed their first docking, and moments later, Tom Stafford and Alexei Leonov shook hands in space — a gesture that some view as a symbolic end of the space race. Stafford and Slayton floated into Soyuz to meet and exchange gifts with Leonov and Kubasov, while Brand remained in Apollo to monitor systems.

The crews received congratulations from Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev, followed by a call from the U.S. president Gerald Ford. The call was a bit unexpected, as it was only supposed to last five minutes, but ended up lasting nine. The president had a draft list of suggested questions, but no one expected he’d actually ask all of them or personally speak with every astronaut and cosmonaut aboard Soyuz. But that’s exactly what he did. The astronauts had to quickly pass around their helmets so each could respond in turn. Nevertheless, the call added warmth and humor to the day.

July 18: Joint Activity

On July 18, Apollo and Soyuz turned into a “Soviet-American TV center in space.” Kubasov led a tour of Soyuz, while Stafford gave a Russian-language tour of Apollo. The crews completed four transfers, taking turns aboard each spacecraft to carry out joint experiments, TV broadcasts, and symbolic activities.

When a Soviet reporter asked to demonstrate the essence of the joint mission, Leonov and Stafford simply held up their countries’ flags — although unintendedly backwards. Kubasov summed it up: “It would be wrong to ask which country's more beautiful. It would be right to say there is nothing more beautiful than our blue planet.”

By the end of the day, everyone had spent meaningful time aboard each other’s spacecraft: Stafford (7h10), Brand (6h30), Slayton (1h35), Leonov (5h43), and Kubasov (4h57). It had been one of the busiest and most heartfelt days of the mission.

July 19: Second Docking, Scientific Experiments & Farewell

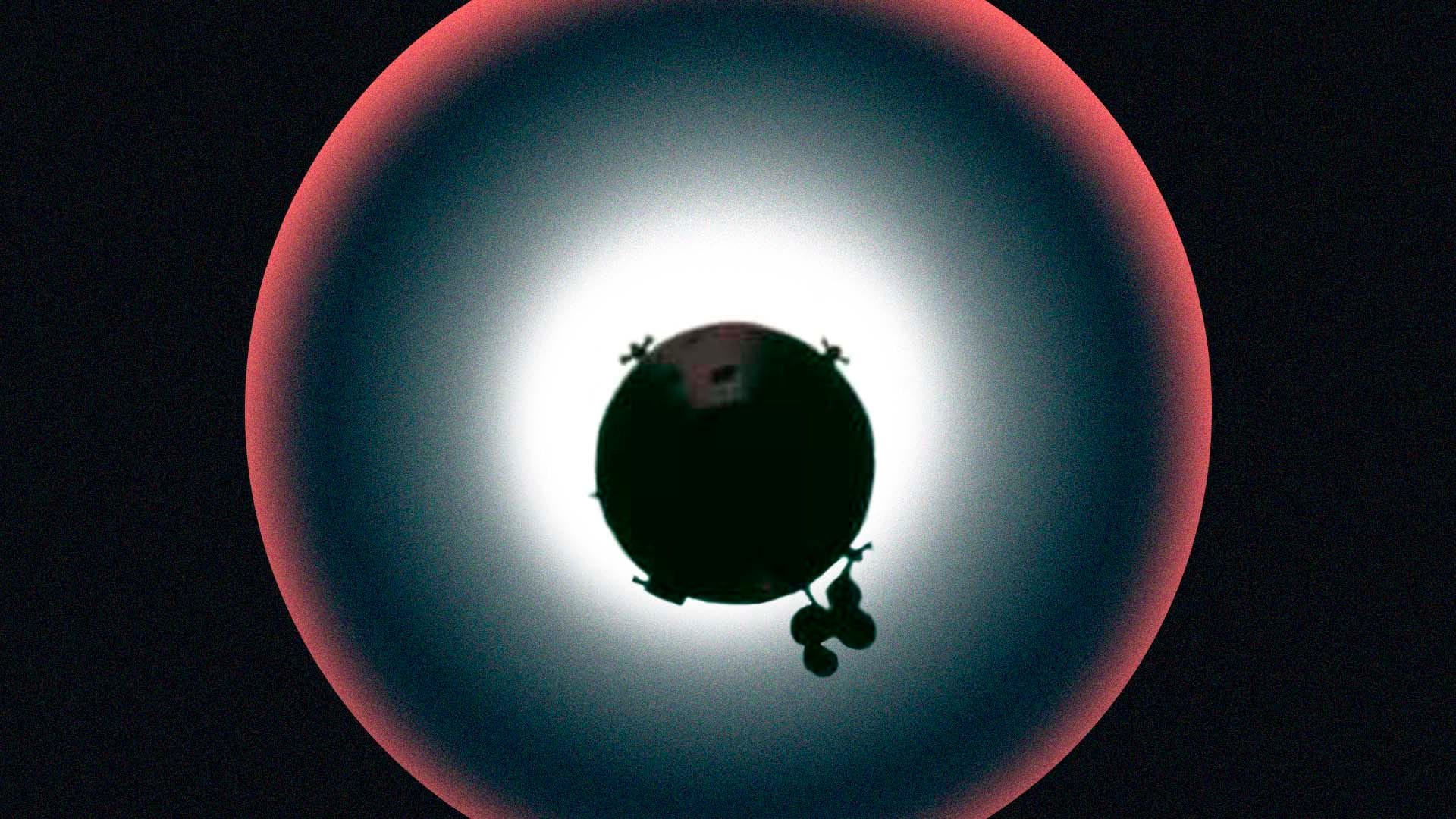

Apollo’s fifth day began a little late, as the crew slept through their planned wake-up song, “Tenderness” by Maya Kristalinskaya. But they were up 15 minutes later and ready to go. At 12:12 GMT, Apollo and Soyuz undocked after 44 hours connected. Apollo then moved between Soyuz and the Sun to create the first ever artificial solar eclipse, allowing the Soviet crew to photograph the Sun’s corona. A second docking followed, with Deke Slayton at the controls. Visibility was poor, but the docking was smooth despite a brief wobble. At 15:26 GMT, the spacecraft undocked again to perform the ultraviolet absorption experiment. Apollo flew around Soyuz in carefully planned paths to measure gases in the upper atmosphere. The task pushed fuel limits and required full crew coordination. Later that afternoon, Apollo fired its engines to move into a new orbit, ending the joint part of the mission.

July 20: Separate Ways

On July 20, Leonov and Kubasov started their day early, performing Earth and solar photography and a fungi experiment, while Apollo was finally awakened by “Tenderness.” The day was calm and science-focused, with both crews working on crystal growth, helium glow, ultraviolet surveys, and furnace tests. They also took a moment to reflect on the sixth anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon landing.

July 21: Soyuz Returns to Earth

On July 21, Soyuz began its descent, followed by smooth module separation and reentry. The capsule landed less than 11 km from its target near Baikonur Cosmodrome. This was the first time that both the launch and landing of a Soviet mission were broadcast on live television. As the capsule descended, Kubasov emerged first, slightly shaky but smiling, followed by Leonov. The confirmation came: “Soyuz has landed safely, and Alexey and Valeriy are outside and in good health.”

July 22-23: Apollo’s Solo Flight

Apollo stayed in orbit a few extra days to carry out 23 independent experiments, with a focus on tracking tectonic activity on Earth. The crew also held a live press conference from orbit, sharing insights on space travel and the mission’s challenges. With trademark humor, Deke Slayton quipped that he hadn’t done anything in space his 91-year-old aunt couldn’t have handled — quite a modest remark.

Afterward, the astronauts donned their suits, vented the docking module tunnel, and released the trash-filled module into space, where it drifted until burning up in Earth’s atmosphere weeks later.

July 24: Apollo’s Final Splashdown

On July 24, Apollo reentered Earth's atmosphere and splashed down in the Pacific Ocean — the final flight of the entire Apollo program. However, trouble struck during descent: toxic nitrogen tetroxide fumes leaked into the cabin, causing the crew to cough and feel unwell. They quickly switched to oxygen masks and completed the landing safely.

Although all three astronauts recovered, they were hospitalized for two weeks. A rough ending, but it didn’t detract from the mission’s success.

Afterword: The Significance Of the Apollo-Soyuz Mission

The Apollo-Soyuz mission proved that space is not just a stage for competition — it can also be a bridge for cooperation. More than half a century later, this historic handshake in space offers us a timeless message — that peace, trust, and science share the same orbit.