February Constellations and Their Brightest Stars

In February, you can observe stunning constellations like Canis Major, Gemini, Auriga, and many others. With the free Star Walk 2 app, finding them takes just seconds — simply point your device at the sky. In this article, you’ll learn which constellations are best to see in February, when to spot them, and what makes each one special.

Contents

- February night sky map for the Northern Hemisphere

- February night sky map for the Southern Hemisphere

- Look to the other side: Circumpolar constellations

- Constellations visible in February: Bottom line

List of February constellations

Each month has its own “best” constellations — those that climb to their highest point in the sky around 9 p.m. local time and thus are easy to observe. In February, such constellations are Canis Major, Auriga, Gemini, Lepus, Columba, Monoceros, Camelopardalis, and Pictor.

The directions below are based on observations made between 9 and 10 p.m. local time, when the sky is fully dark. For each constellation, you’ll also find the range of latitudes from which it can be seen. To quickly locate any constellation in the sky, use the Star Walk 2 app.

Canis Major

- Brightness: ☆☆☆

- Visible between: 60°N and 90°S

- Brightest star: Sirius (mag -1.4)

- Notable deep-sky object: Little Beehive Cluster (M41, mag 4.5)

How to find Canis Major in the February night sky

The constellation Canis Major (“the Great Dog”) stands out thanks to Sirius — the brightest star in the night sky.

In the Northern Hemisphere, first locate Orion’s Belt and then extend its line downward to the bright point of Sirius. This star marks the head of the celestial Great Dog, with the rest of the constellation stretching below it.

In the Southern Hemisphere, Canis Major climbs much higher in the sky during February evenings and becomes one of the most eye-catching constellations. It can be found the same way — by extending the line of the Orion’s Belt toward Sirius.

Myth of the Canis Major constellation

In Greek mythology, Canis Major is often identified with Laelaps, a magical hunting dog that was destined to always catch its prey. During an endless chase, both the dog and its quarry were turned to stone, and Zeus later placed Laelaps among the stars, preserving its speed and determination forever.

More commonly, the constellation Canis Major is linked to Orion’s faithful hunting dog. Together with Canis Minor, the smaller dog, it follows the great hunter through the night sky.

Auriga

- Brightness: ☆☆☆

- Visible between: 90°N and 40°S

- Brightest star: Capella (mag 0.1)

- Notable deep-sky object: Broken Heart Cluster (NGC 2281, mag 5.4)

How to find Auriga in the February night sky

The constellation Auriga (“the Charioteer”) is easy to spot thanks to Capella, one of the brightest stars in the night sky. Capella’s steady yellow-white glow makes it a prominent landmark on February evenings.

In the Northern Hemisphere, Auriga is positioned high in the sky during February. Once Capella is located, look for a loose pentagon of stars surrounding it — they outline the shape of the celestial charioteer. The constellation Auriga is also situated near Gemini and Taurus, which can help with orientation.

In the Southern Hemisphere, Auriga appears lower above the horizon but remains noticeable because of Capella’s brightness. From mid-southern latitudes, the star stands out clearly, even though the rest of the constellation stays relatively low.

Myth of the Auriga constellation

In Greek mythology, Auriga is commonly associated with Erichthonius, a legendary king of Athens credited with inventing the four-horse chariot. According to the myth, Zeus placed him among the stars to honor his ingenuity and skill as a charioteer.

In the night sky, Auriga is depicted with a chariot and a young goat, represented by Capella — whose name means “the little she-goat” in Latin — along with nearby stars known as the Kids. Together, they form a distinctive figure in the winter sky.

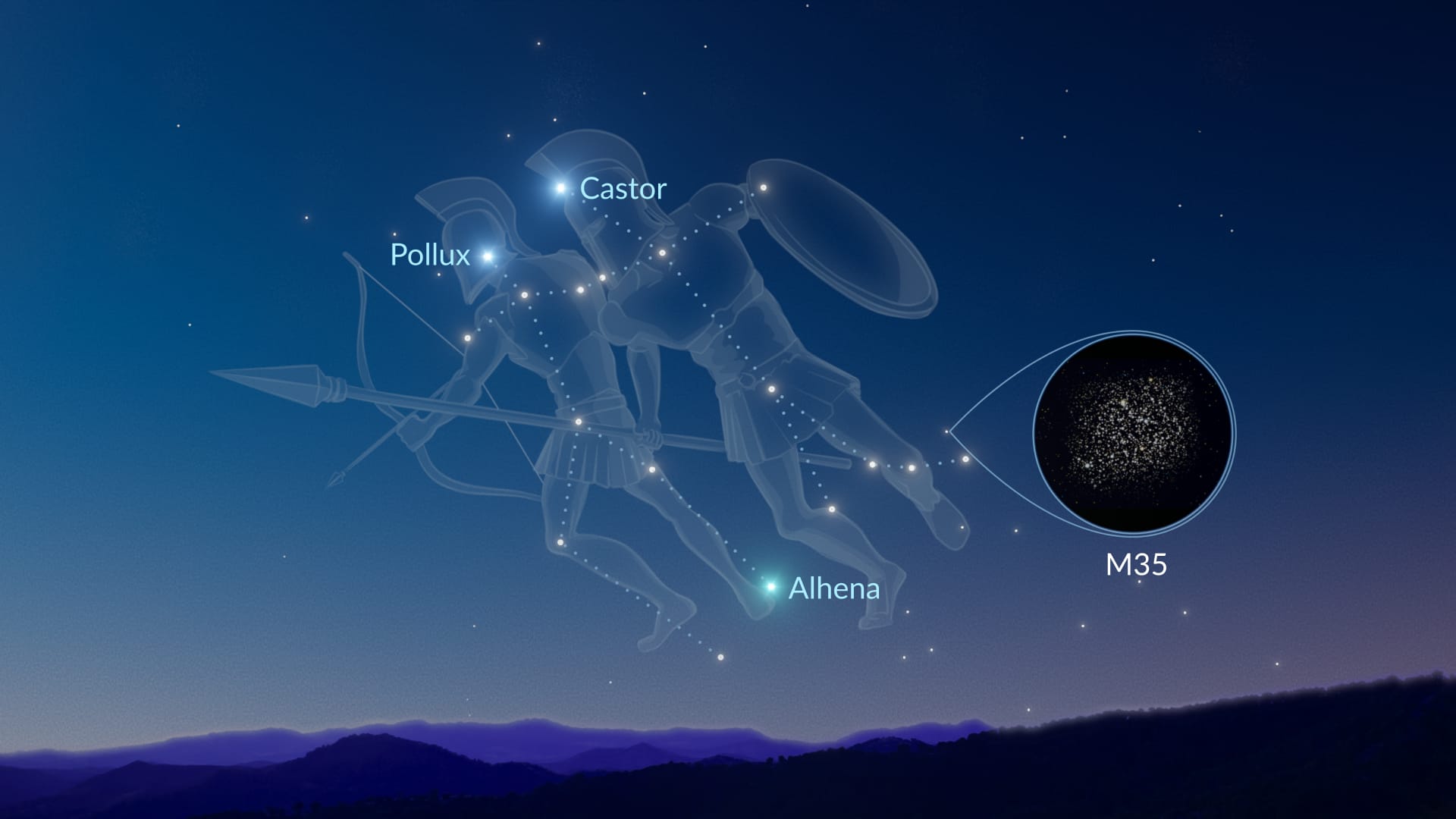

Gemini

- Brightness: ☆☆

- Visible between: 90°N and 60°S

- Brightest star: Pollux (mag 1.1)

- Notable deep-sky object: Shoe-Buckle Cluster (M35, mag 5.1)

How to find Gemini in the February night sky

Gemini (“the Twins”) is easy to recognize thanks to its two bright “twin” stars, Castor and Pollux. Also, if you can spot the constellation Orion, you’re already close, as Gemini is adjacent to Orion.

In the Northern Hemisphere, Gemini appears high above the horizon on February evenings. Start by finding Orion’s Belt, then look upward and slightly eastward to find two bright stars of similar brightness — these are Castor and Pollux. From there, you can trace two roughly parallel lines of stars extending downward, forming the bodies of the celestial twins.

In the Southern Hemisphere, Gemini appears lower above the horizon but remains clearly visible during February evenings. From mid-southern latitudes, the constellation doesn’t climb very high, yet Castor and Pollux still stand out as a distinctive pair of stars. Farther south, Gemini’s lower stars may dip below the horizon.

Myth of the Gemini constellation

In Greek mythology, Gemini represents the twins Castor and Pollux (also known as the Dioscuri). Although they were raised together, the twins had different origins: Castor was mortal, while Pollux was the immortal son of Zeus. The brothers were inseparable and shared many adventures, including joining Jason and the Argonauts.

When Castor was killed in battle, Pollux was devastated and begged Zeus to let him share his immortality with his brother. Moved by their bond, Zeus placed them both in the sky as the constellation Gemini, allowing them to remain together forever.

Lepus

- Brightness: ☆☆

- Visible between: 60°N and 90°S

- Brightest star: Arneb (mag 2.6)

- Notable deep-sky object: Globular cluster M79 (mag 7.7)

How to find Lepus in the February night sky

The constellation Lepus (“the Hare”) lies near Orion and is best seen under dark skies, as its stars are relatively faint.

In the Northern Hemisphere, Lepus appears quite low above the horizon. Once you find Orion, look just below its bright outline to spot a compact group of stars forming a flattened, quadrilateral shape — this marks the body of the celestial Hare.

In the Southern Hemisphere, Lepus is positioned higher in the sky and is easier to observe. From mid-southern latitudes, the constellation stands well above the horizon, allowing its full shape to be traced more clearly, especially away from city lights.

Myth of the Lepus constellation

In Greek mythology, Lepus represents a hare that was chased across the sky by Orion and his hunting dogs. The constellation’s placement directly beneath Orion reflects this eternal pursuit. Greek scholar Eratosthenes tells us that it was Hermes who placed the hare in the sky — because of its swiftness.

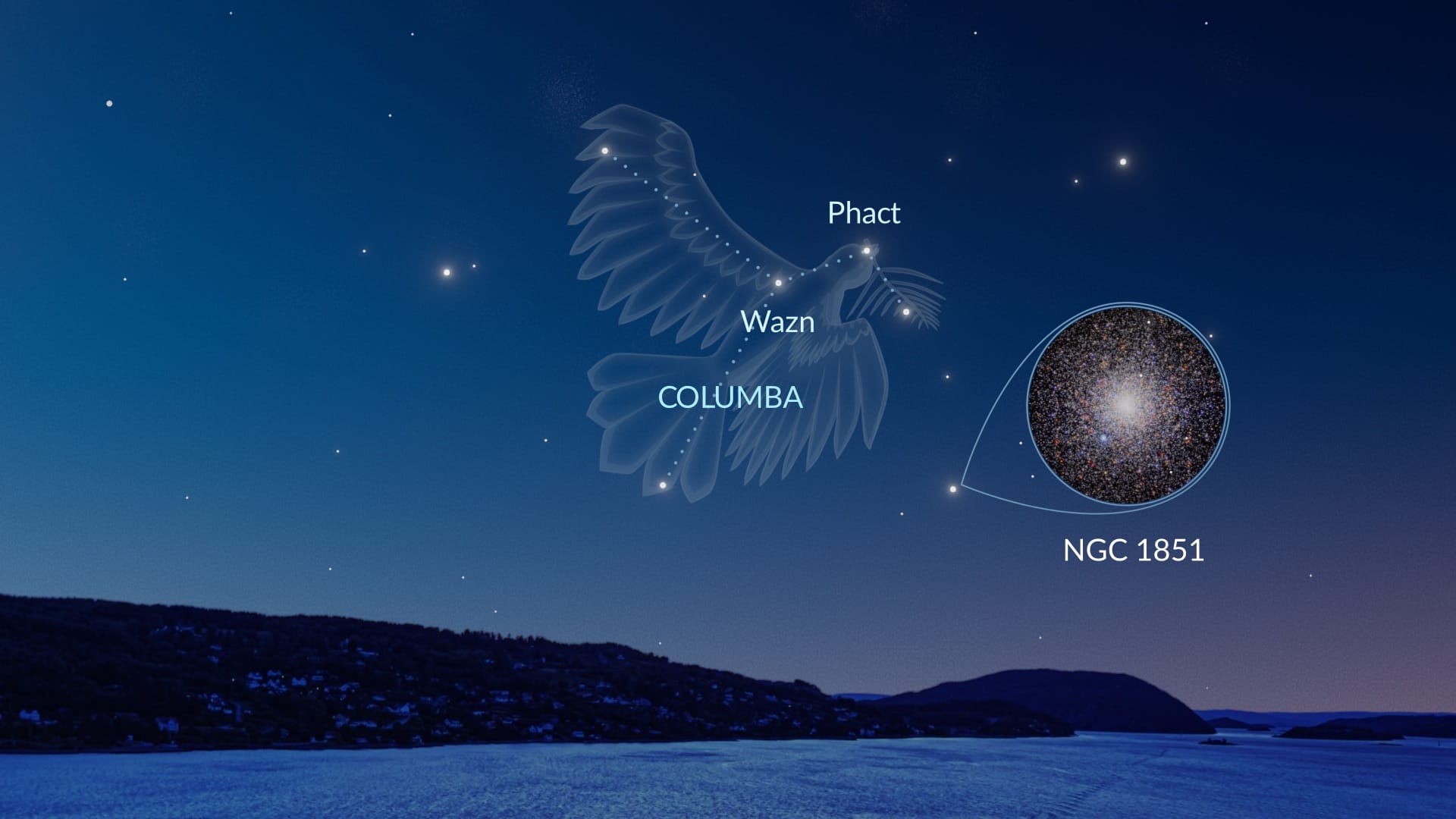

Columba

- Brightness: ☆☆

- Visible between: 45°N and 90°S

- Brightest star: Phact (mag 2.6)

- Notable deep-sky object: Globular cluster NGC 1851 (mag 7.3)

How to find Columba in the February night sky

The constellation Columba (“the Dove”) is a small and relatively faint star pattern located near Canis Major and Lepus.

In the Northern Hemisphere, Columba is more challenging to observe, as it sits very low above the horizon — or doesn’t rise at all in some locations. To find Columba, you should first locate Sirius in Canis Major. After that, look slightly to the south where you’ll see a compact group of dim stars forming the outline of the Dove.

In the Southern Hemisphere, Columba stands much higher in the sky and is easier to trace. You can use the bright star Sirius to find it as well.

Myth of the Columba constellation

Columba is sometimes associated with the dove sent out by Noah in the biblical story of the Great Flood, symbolizing hope and renewal after the waters receded. Another interpretation links the constellation to a dove that guided Jason and the Argonauts through the dangerous Clashing Rocks.

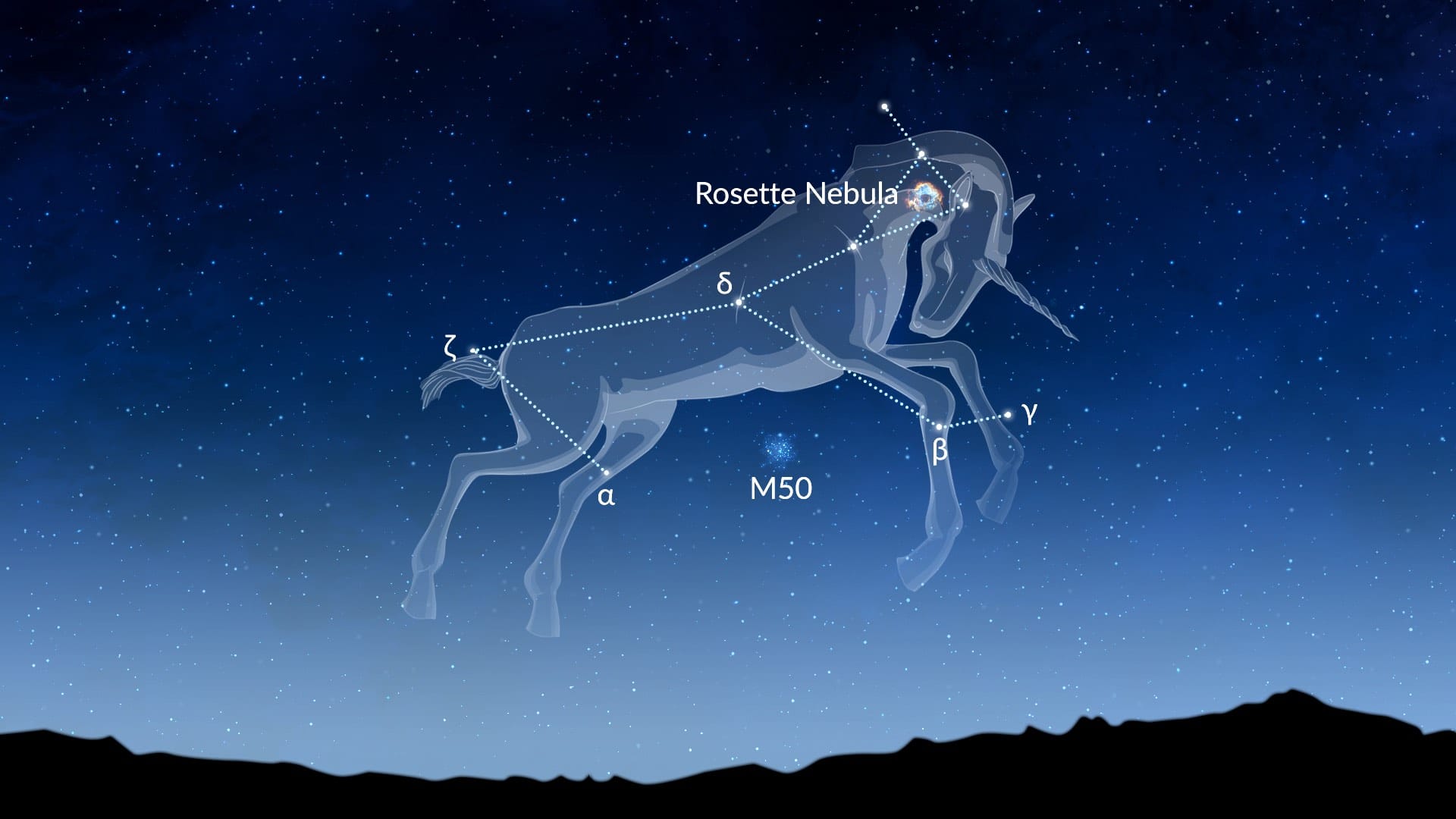

Monoceros

- Brightness: ☆

- Visible between: 75°N and 90°S

- Brightest star: Beta Monocerotis (mag 3.8)

- Notable deep-sky object: Heart-shaped Cluster (M50, mag 5.9)

How to find Monoceros in the February night sky

The constellation Monoceros (“the Unicorn”) is a faint star pattern best explored with the help of nearby, brighter asterisms and constellations.

In the Northern Hemisphere, Monoceros is more challenging to observe, as it appears relatively low above the horizon. To find Monoceros, first locate the bright Winter Triangle, formed by Sirius, Betelgeuse, and Procyon. Monoceros lies inside this triangle, in the region between Orion and Canis Major. Because the constellation lacks bright stars, dark skies are essential.

In the Southern Hemisphere, Monoceros stands higher in the sky and is easier to trace. You can use the same bright stars of the Winter Triangle to locate it.

Myth of the Monoceros constellation

Unlike many constellations, Monoceros does not originate from ancient mythology. It was introduced in the early 17th century by the Dutch astronomer Petrus Plancius and later popularized by Johannes Hevelius. Monoceros represents a unicorn, a mythical creature symbolizing purity and mystery.

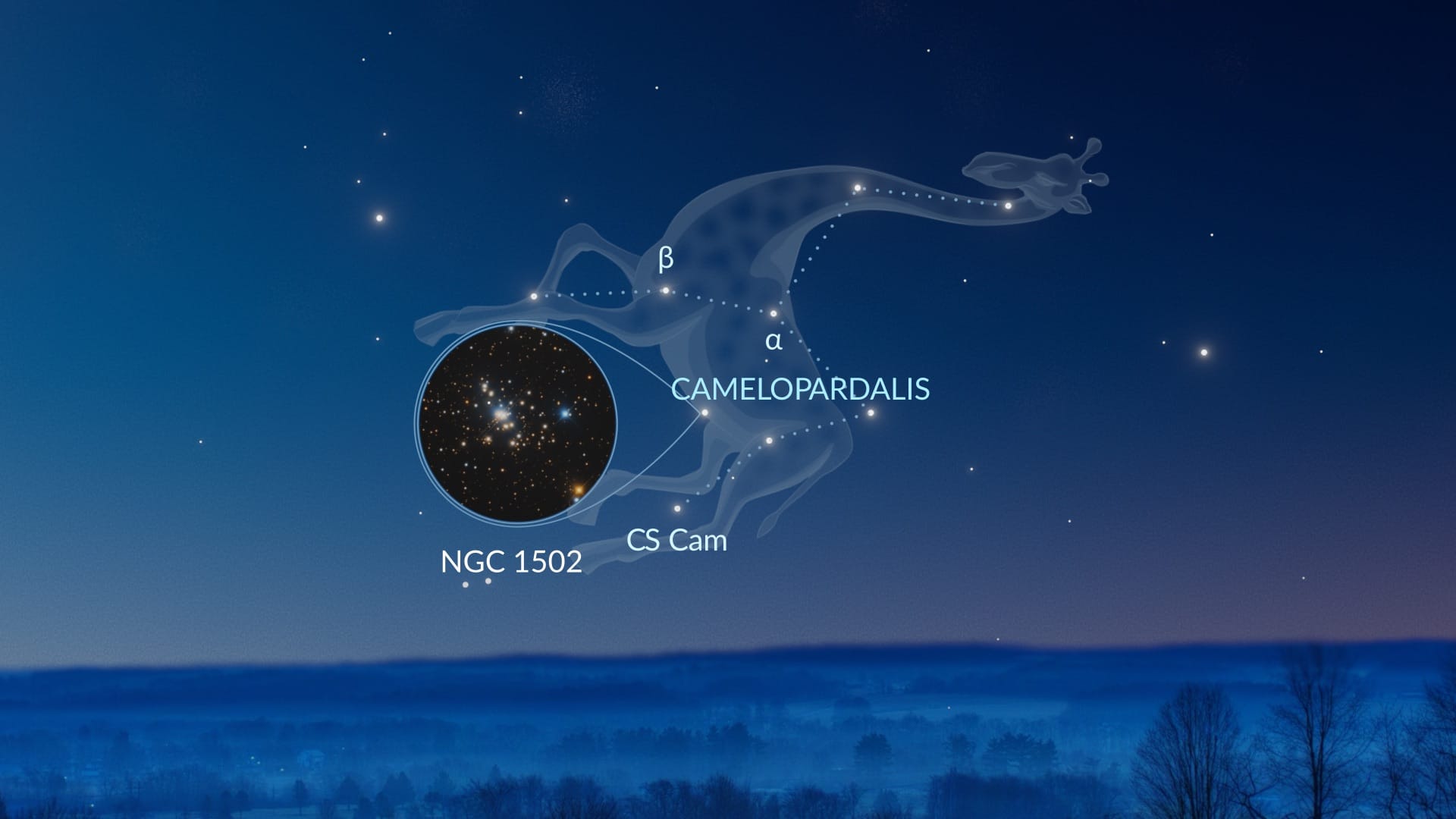

Camelopardalis

- Brightness: ☆

- Visible between: 90°N and 10°S

- Brightest star: Beta Camelopardalis (mag 4.0)

- Notable deep-sky object: Golden Harp Cluster (NGC 1502, mag 6.0)

How to find Camelopardalis in the February night sky

The constellation Camelopardalis (“the Giraffe”) is one of the faintest in the sky and lacks bright stars, so it’s best approached using nearby, more noticeable constellations as guides.

In the Northern Hemisphere, Camelopardalis is circumpolar from many locations and never sets below the horizon. To locate it, first find the familiar Big Dipper. From there, look toward Polaris — Camelopardalis lies in the broad, faint region of sky surrounding the star, bordered by the Ursa Major and Cassiopeia.

In the Southern Hemisphere, Camelopardalis stays very low above the horizon and is difficult to observe. From locations close to the equator, only its southernmost stars may briefly rise.

Myth of the Camelopardalis constellation

Camelopardalis does not come from classical Greek mythology. It was introduced in the early 17th century by the Dutch astronomer Petrus Plancius to represent a giraffe, an exotic animal that was little known in Europe at the time. The constellation’s Latin name comes from a blend of “camel” and “leopard,” reflecting early beliefs that a giraffe combined features of both animals.

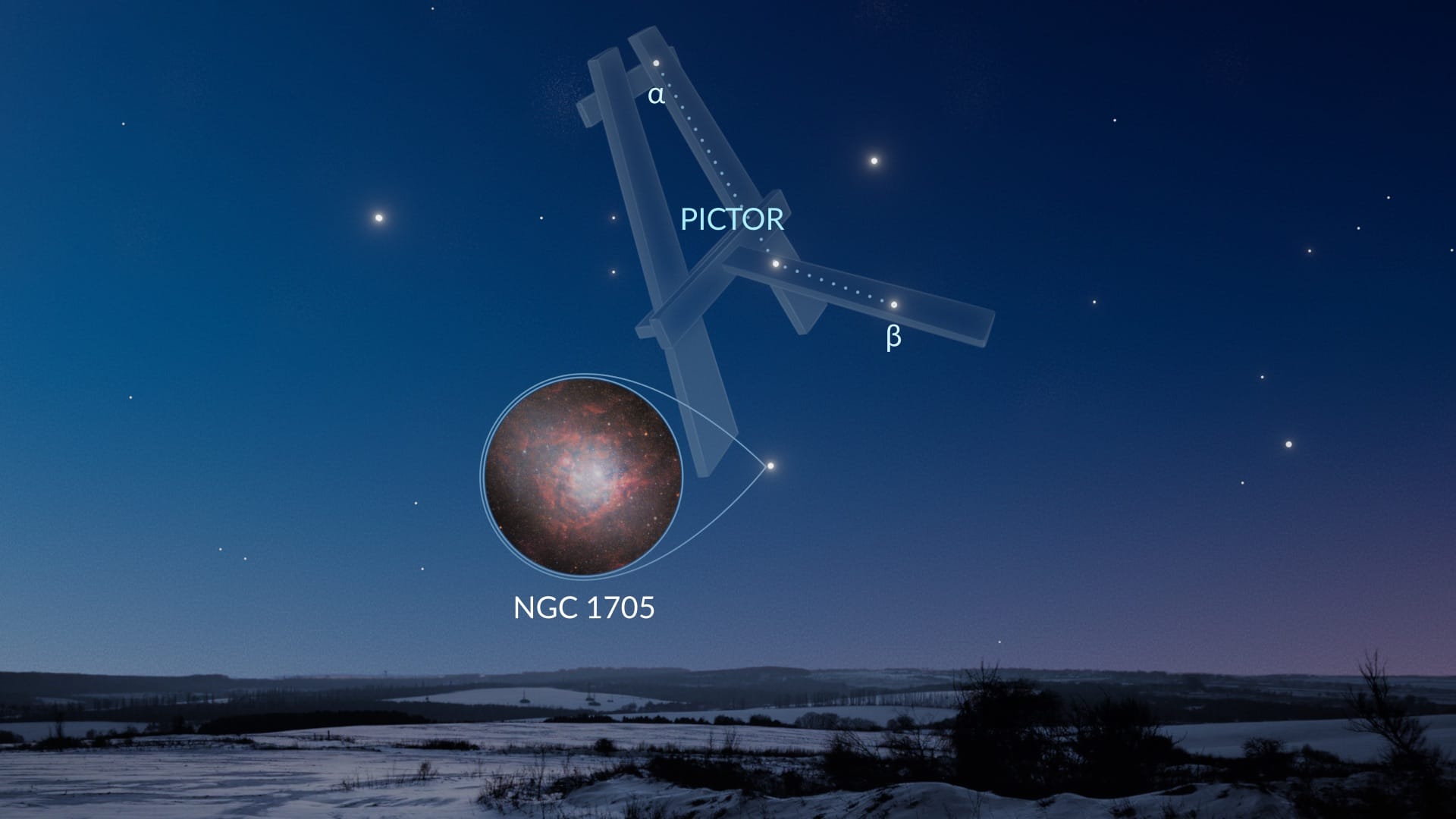

Pictor

- Brightness: ☆

- Visible between: 25°N and 90°S

- Brightest star: Alpha Pictoris (mag 3.3)

- Notable deep-sky object: Dwarf galaxy NGC 1705 (mag 12.5)

How to find Pictor in the February night sky

The constellation Pictor (“the Painter”) is a small and faint southern constellation, best observed from locations south of the equator.

In the Northern Hemisphere, Pictor is very difficult or impossible to see. From most northern locations, it stays below the horizon; only observers very close to the equator may glimpse its northernmost stars very low in the southern sky.

In the Southern Hemisphere, Pictor is well placed for observation. Start by finding Canopus, the bright star in Carina, or Achernar in Eridanus. Pictor lies between these two landmarks, forming a subtle pattern of faint stars.

Myth of the Pictor constellation

Pictor does not come from ancient mythology. It was introduced in the 18th century by the French astronomer Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille, who created several new southern constellations to fill previously unmapped regions of the sky. The constellation represents an easel or painter’s tool, reflecting the scientific instruments and artistic motifs favored during the Age of Enlightenment.

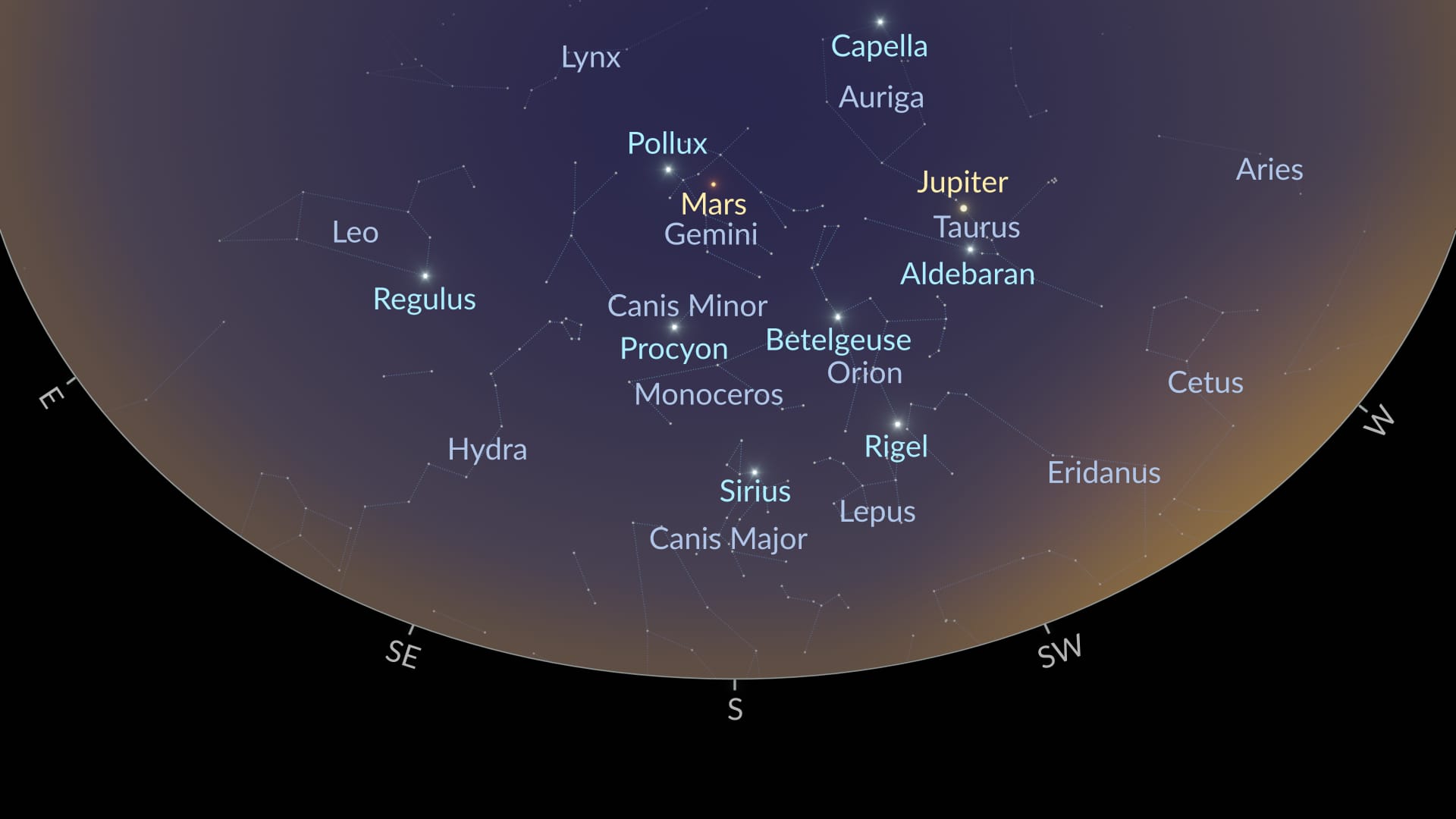

February night sky map for the Northern Hemisphere

Here is the sky view for February 2026. It shows what is above the southern horizon at mid-evening for mid-northern latitudes.

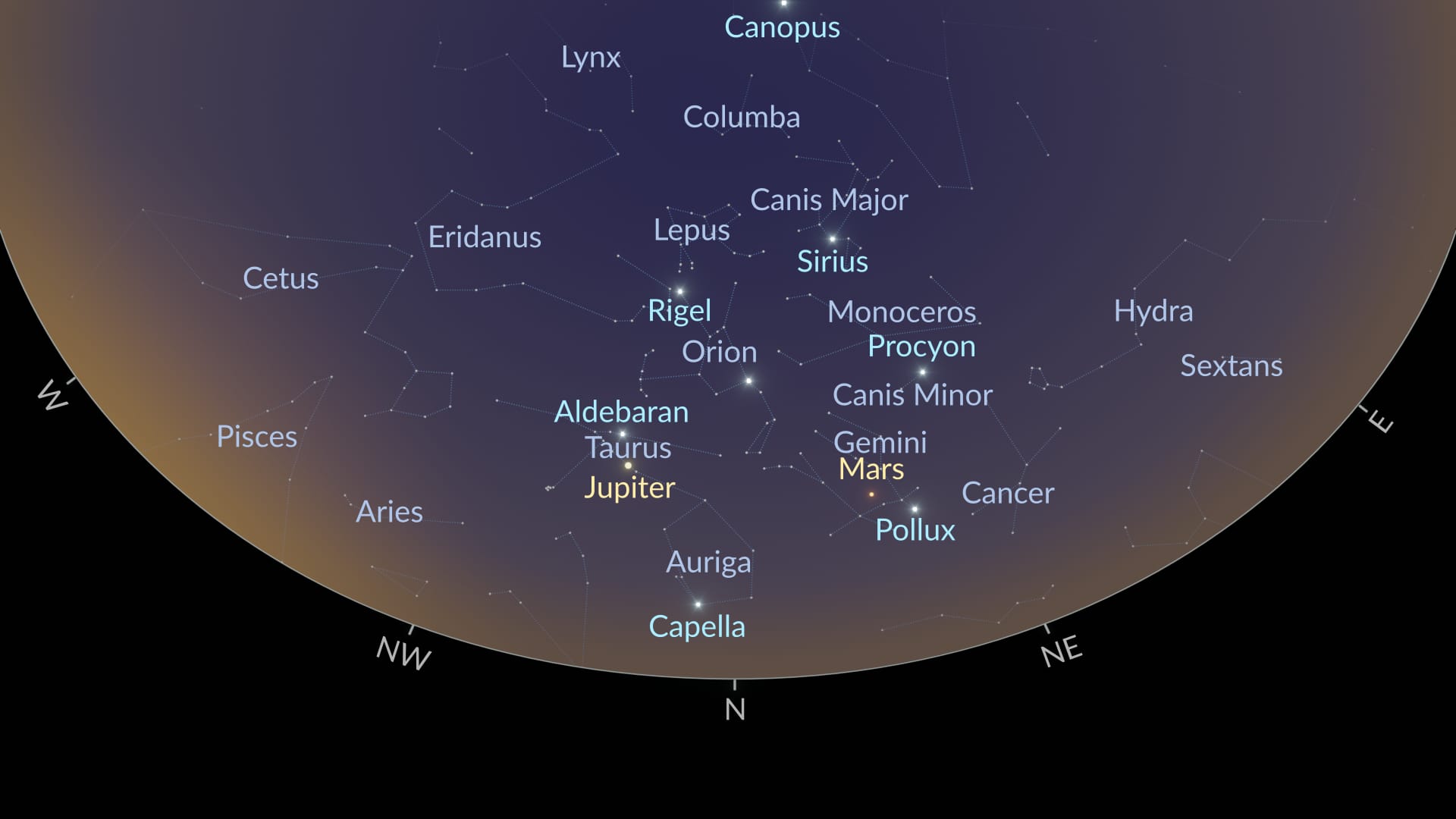

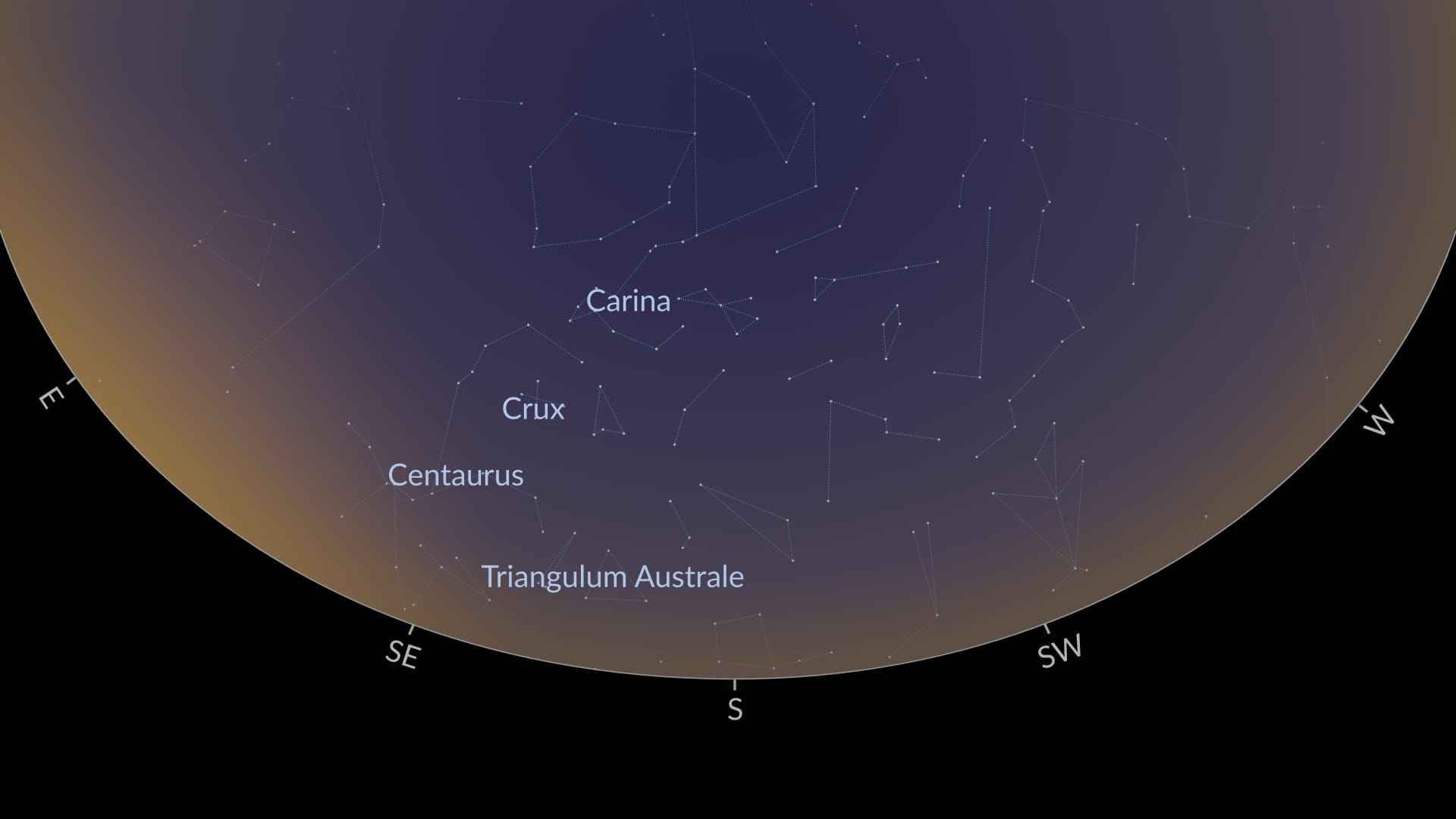

February night sky map for the Southern Hemisphere

Here is the sky view for February 2026. It shows what is above the northern horizon at mid-evening for mid-southern latitudes.

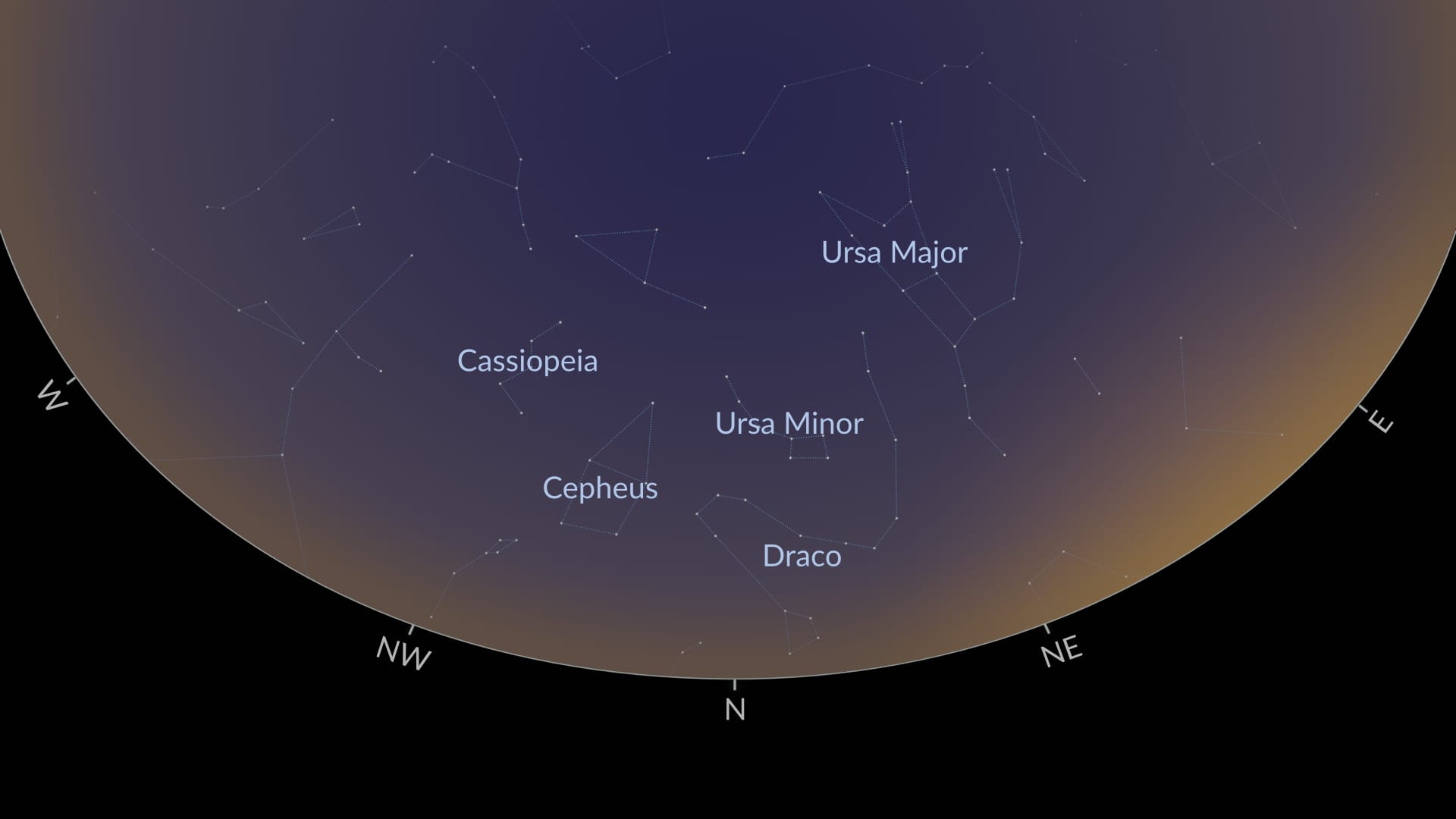

Look to the other side: Circumpolar constellations

Why do we only look at the southern sky for the Northern Hemisphere and the northern sky for the Southern Hemisphere? The thing is, the opposite side of the sky is dominated by constellations that are visible all year round. Their positions shift with the seasons, but they never dip below the horizon. These are known as the circumpolar constellations.

In the Northern Hemisphere, the circumpolar constellations are Ursa Major, Ursa Minor, Cassiopeia, Cepheus, and Draco.

In the Southern Hemisphere, the circumpolar constellations are Carina, Crux, Centaurus, and Triangulum Australe.

If you want to learn more about circumpolar constellations, read our dedicated article.

Constellations visible in February: Bottom line

The February night sky offers eight fantastic constellations for you to explore. Find Canis Major, spot the celestial hare Lepus nearby, and trace fainter patterns like Columba and Monoceros under dark skies. Not sure where to start? Download the free Star Walk 2 app app and let it be your night sky guide.

February is also a perfect month to view a number of galaxies, nebulae, and star clusters. These include the Large Magellanic Cloud, the Hand Cluster, and the Cigar Galaxy. Read our guide to learn more!